3.3 Data structures

Now that you’ve been introduced to some of the most important classes of data in R, let’s have a look at some of main structures that we have for storing these data.

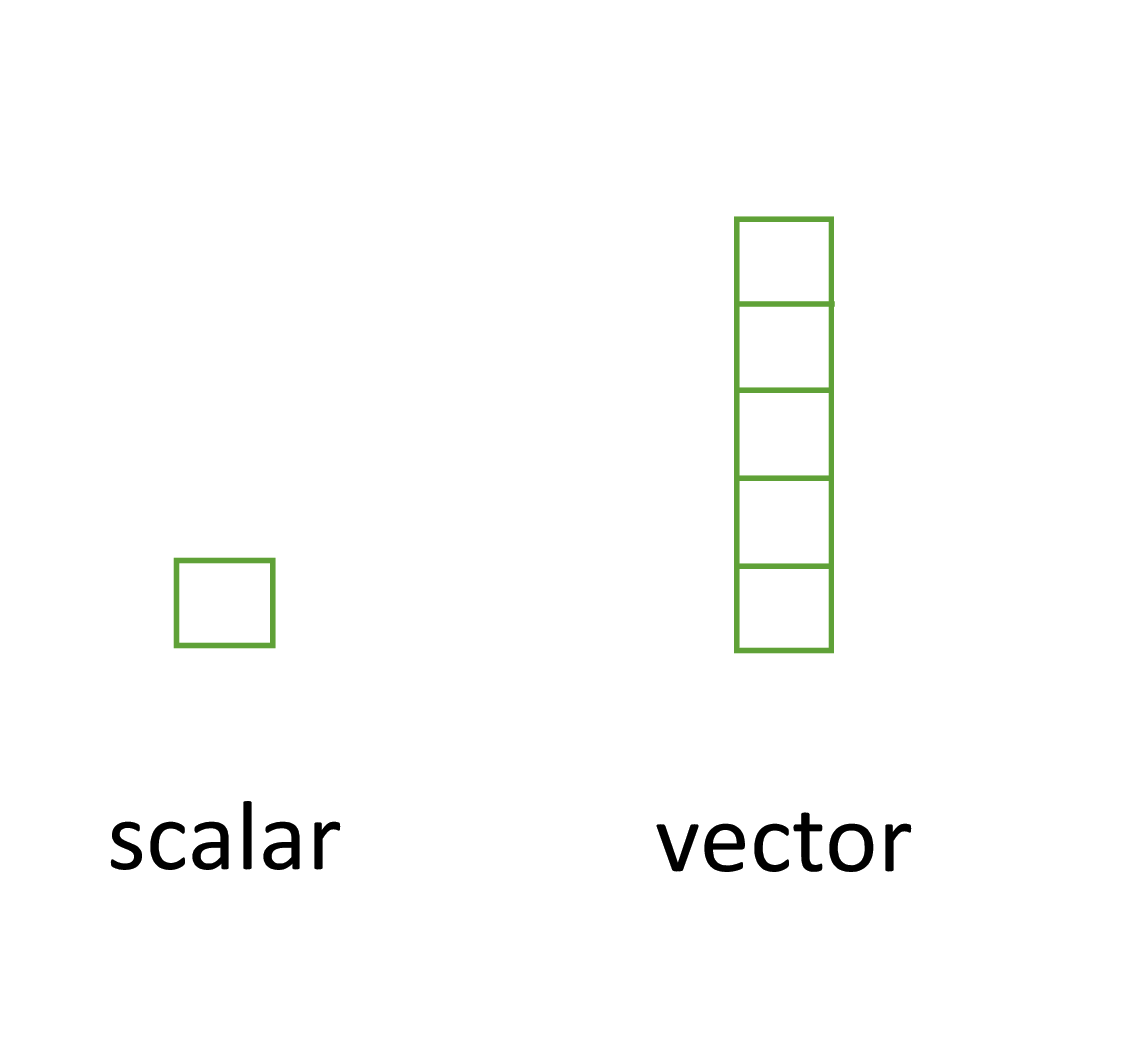

3.3.1 Scalars and vectors

Perhaps the simplest type of data structure is the vector. You’ve already been introduced to vectors in Chapter 2 although some of the vectors you created only contained a single value. Vectors that have a single value (length 1) are called scalars. Vectors can contain numbers, characters, factors or logicals, but the key thing to remember is that all the elements inside a vector must be of the same class. In other words, vectors can contain either numbers, characters or logicals but not mixtures of these types of data. There is one important exception to this, you can include NA (remember this is special type of logical) to denote missing data in vectors with other data types.

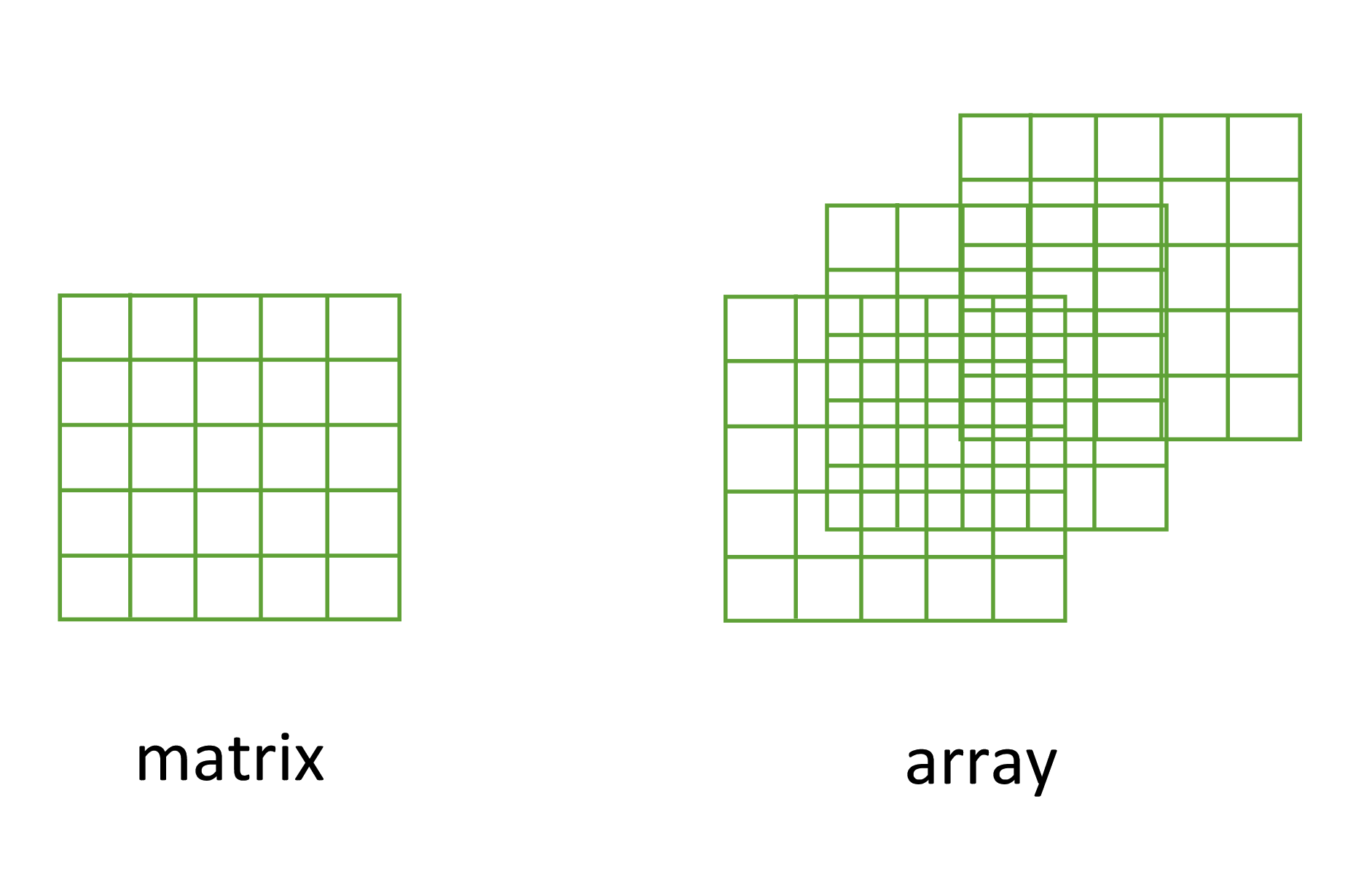

3.3.2 Matrices and arrays

Another useful data structure used in many disciplines is the matrix. A matrix is simply a vector that has additional attributes called dimensions. Arrays are just multidimensional matrices. Again, matrices and arrays must contain elements all of the same data class.

A convenient way to create a matrix or an array is to use the matrix() and array() functions respectively. Below, we will create a matrix from a sequence 1 to 16 in four rows (nrow = 4) and fill the matrix row-wise (byrow = TRUE) rather than the default column-wise. When using the array() function we define the dimensions using the dim = argument, in our case 2 rows, 4 columns in 2 different matrices.

my_mat <- matrix(1:16, nrow = 4, byrow = TRUE)

my_mat

## [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4]

## [1,] 1 2 3 4

## [2,] 5 6 7 8

## [3,] 9 10 11 12

## [4,] 13 14 15 16

my_array <- array(1:16, dim = c(2, 4, 2))

my_array

## , , 1

##

## [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4]

## [1,] 1 3 5 7

## [2,] 2 4 6 8

##

## , , 2

##

## [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4]

## [1,] 9 11 13 15

## [2,] 10 12 14 16Sometimes it’s also useful to define row and column names for your matrix but this is not a requirement. To do this use the rownames() and colnames() functions.

rownames(my_mat) <- c("A", "B", "C", "D")

colnames(my_mat) <- c("a", "b", "c", "d")

my_mat

## a b c d

## A 1 2 3 4

## B 5 6 7 8

## C 9 10 11 12

## D 13 14 15 16Once you’ve created your matrices you can do useful stuff with them and as you’d expect, R has numerous built in functions to perform matrix operations. Some of the most common are given below. For example, to transpose a matrix we use the transposition function t()

my_mat_t <- t(my_mat)

my_mat_t

## A B C D

## a 1 5 9 13

## b 2 6 10 14

## c 3 7 11 15

## d 4 8 12 16To extract the diagonal elements of a matrix and store them as a vector we can use the diag() function

my_mat_diag <- diag(my_mat)

my_mat_diag

## [1] 1 6 11 16The usual matrix addition, multiplication etc can be performed. Note the use of the %*% operator to perform matrix multiplication.

mat.1 <- matrix(c(2, 0, 1, 1), nrow = 2) # notice that the matrix has been filled

mat.1 # column-wise by default

## [,1] [,2]

## [1,] 2 1

## [2,] 0 1

mat.2 <- matrix(c(1, 1, 0, 2), nrow = 2)

mat.2

## [,1] [,2]

## [1,] 1 0

## [2,] 1 2

mat.1 + mat.2 # matrix addition

## [,1] [,2]

## [1,] 3 1

## [2,] 1 3

mat.1 * mat.2 # element by element products

## [,1] [,2]

## [1,] 2 0

## [2,] 0 2

mat.1 %*% mat.2 # matrix multiplication

## [,1] [,2]

## [1,] 3 2

## [2,] 1 23.3.3 Lists

The next data structure we will quickly take a look at is a list. Whilst vectors and matrices are constrained to contain data of the same type, lists are able to store mixtures of data types. In fact we can even store other data structures such as vectors and arrays within a list or even have a list of a list. This makes for a very flexible data structure which is ideal for storing irregular or non-rectangular data (see Chapter 7 for an example).

To create a list we can use the list() function. Note how each of the three list elements are of different classes (character, logical, and numeric) and are of different lengths.

list_1 <- list(c("black", "yellow", "orange"),

c(TRUE, TRUE, FALSE, TRUE, FALSE, FALSE),

matrix(1:6, nrow = 3))

list_1

## [[1]]

## [1] "black" "yellow" "orange"

##

## [[2]]

## [1] TRUE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE

##

## [[3]]

## [,1] [,2]

## [1,] 1 4

## [2,] 2 5

## [3,] 3 6Elements of the list can be named during the construction of the list

list_2 <- list(colours = c("black", "yellow", "orange"),

evaluation = c(TRUE, TRUE, FALSE, TRUE, FALSE, FALSE),

time = matrix(1:6, nrow = 3))

list_2

## $colours

## [1] "black" "yellow" "orange"

##

## $evaluation

## [1] TRUE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE

##

## $time

## [,1] [,2]

## [1,] 1 4

## [2,] 2 5

## [3,] 3 6or after the list has been created using the names() function

names(list_1) <- c("colours", "evaluation", "time")

list_1

## $colours

## [1] "black" "yellow" "orange"

##

## $evaluation

## [1] TRUE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE

##

## $time

## [,1] [,2]

## [1,] 1 4

## [2,] 2 5

## [3,] 3 63.3.4 Data frames

Take a look at this video for a quick introduction to data frame objects in R

By far the most commonly used data structure to store data in is the data frame. A data frame is a powerful two-dimensional object made up of rows and columns which looks superficially very similar to a matrix. However, whilst matrices are restricted to containing data all of the same type, data frames can contain a mixture of different types of data. Typically, in a data frame each row corresponds to an individual observation and each column corresponds to a different measured or recorded variable. This setup may be familiar to those of you who use LibreOffice Calc or Microsoft Excel to manage and store your data. Perhaps a useful way to think about data frames is that they are essentially made up of a bunch of vectors (columns) with each vector containing its own data type but the data type can be different between vectors.

We can construct a data frame from existing data objects such as vectors using the data.frame() function. As an example, let’s create three vectors p.height, p.weight and p.names and include all of these vectors in a data frame object called dataf.

p.height <- c(180, 155, 160, 167, 181)

p.weight <- c(65, 50, 52, 58, 70)

p.names <- c("Joanna", "Charlotte", "Helen", "Karen", "Amy")

dataf <- data.frame(height = p.height, weight = p.weight, names = p.names)

dataf

## height weight names

## 1 180 65 Joanna

## 2 155 50 Charlotte

## 3 160 52 Helen

## 4 167 58 Karen

## 5 181 70 AmyYou’ll notice that each of the columns are named with variable name we supplied when we used the data.frame() function. It also looks like the first column of the data frame is a series of numbers from one to five. Actually, this is not really a column but the name of each row. We can check this out by getting R to return the dimensions of the dataf object using the dim() function. We see that there are 5 rows and 3 columns.

dim(dataf) # 5 rows and 3 columns

## [1] 5 3Another really useful function which we use all the time is str() which will return a compact summary of the structure of the data frame object (or any object for that matter).

str(dataf)

## 'data.frame': 5 obs. of 3 variables:

## $ height: num 180 155 160 167 181

## $ weight: num 65 50 52 58 70

## $ names : chr "Joanna" "Charlotte" "Helen" "Karen" ...The str() function gives us the data frame dimensions and also reminds us that dataf is a data.frame type object. It also lists all of the variables (columns) contained in the data frame, tells us what type of data the variables contain and prints out the first five values. We often copy this summary and place it in our R scripts with comments at the beginning of each line so we can easily refer back to it whilst writing our code. We showed you how to comment blocks in RStudio here.

Also notice that R has automatically decided that our p.names variable should be a character (chr) class variable when we first created the data frame. Whether this is a good idea or not will depend on how you want to use this variable in later analysis. If we decide that this wasn’t such a good idea we can change the default behaviour of the data.frame() function by including the argument stringsAsFactors = TRUE. Now our strings are automatically converted to factors.

p.height <- c(180, 155, 160, 167, 181)

p.weight <- c(65, 50, 52, 58, 70)

p.names <- c("Joanna", "Charlotte", "Helen", "Karen", "Amy")

dataf <- data.frame(height = p.height, weight = p.weight, names = p.names,

stringsAsFactors = TRUE)

str(dataf)

## 'data.frame': 5 obs. of 3 variables:

## $ height: num 180 155 160 167 181

## $ weight: num 65 50 52 58 70

## $ names : Factor w/ 5 levels "Amy","Charlotte",..: 4 2 3 5 1